There has been a lot of progress in natural language understanding during the last years. Let it be the rise of AI assistants like ChatGPT or most recently in foundational models like ModernBERT. Despite their success and being often a synonym for artificial intelligence, many “AI-based” application in the industry are still driven by more traditional models like Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT) – e.g. XGBoost and LightGBM. These traditional models excel at processing tabular data (like product attributes or user behavior metrics). They’re also easier to train and require less computing power than transformer models, making them cheaper to run and simpler to implement.

However, real-world applications typically involve both traditional tabular data (categorical or numerical attributes) and textual information. This combination creates a challenge: how can we integrate GBDTs and (large) language models to leverage the powerful text understanding capabilities of language models while maintaining the efficiency of decision trees?

Let’s consider a simple example of an e-commerce product dataset that combines both structured data and text:

| Product ID | Category | Price ($) | Avg. Rating | Product Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1045 | Electronics | 799.99 | 4.2 | Lightweight laptop with 16GB RAM, SSD storage, and all-day battery life. Perfect for professionals on the go. |

| P2371 | Home & Kitchen | 49.99 | 4.7 | Stainless steel coffee maker with programmable timer and auto-shutoff safety feature. |

| P3082 | Clothing | 29.95 | 3.8 | Classic fit cotton t-shirt available in multiple colors. Pre-shrunk fabric with reinforced seams. |

| P4256 | Sports | 124.50 | 4.5 | Waterproof hiking boots with ankle support and slip-resistant tread for all terrain conditions. |

In this dataset, the ‘Product ID’, ‘Category’, ‘Price’, and ‘Avg. Rating’ are traditional tabular features that GBDTs handle effectively. The ‘Product Description’ field contains rich textual information that LLMs can better understand.

A seemingly straightforward approach is to incorporate LLM-generated embeddings as features in GBDT models. This, however, rarely works well in practice due to the high dimensionality of these embeddings, which requires many splits while building the tree ensemble. While dimension reduction techniques like SVD can address this challenge, they often sacrifice important semantic information in the process.

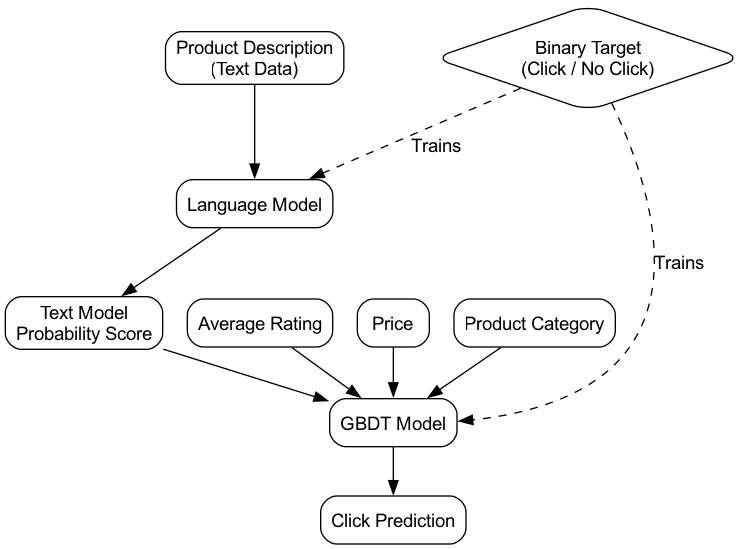

A better approach is to train a separate language model on the text and then use its output as one or more features for training the GBDT model. For example, a BERT model can learn the relationship between product descriptions and user interactions (such as clicks or add-to-cart actions). A simple way to implement this is by modeling it as a binary classification problem that estimates the probability of interaction between users and products. This probability can then serve as a feature for the subsequent GBDT model, whose role is to fine-tune the language model’s output by incorporating additional structured data (such as average rating, price, and product category).

The following self-contained code illustrates this principle with a simple TF-IDF + Logistic Regression language model, which often serves as an excellent baseline:

# /// script

# dependencies = [

# "pandas==2.2.3",

# "scikit-learn==1.6.1",

# "xgboost==2.1.4"

# ]

# ///

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.base import BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

class TextEncoder(BaseEstimator, TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self, text_column):

self.text_column = text_column

self.tfidf = TfidfVectorizer(max_features=1000)

self.model = LogisticRegression()

def fit(self, X, y):

text_data = X[self.text_column]

X_tfidf = self.tfidf.fit_transform(text_data)

self.model.fit(X_tfidf, y)

return self

def transform(self, X):

text_data = X[self.text_column]

X_tfidf = self.tfidf.transform(text_data)

probs = self.model.predict_proba(X_tfidf)[:, 1]

X_transformed = X.copy()

X_transformed['text_model_prob'] = probs

return X_transformed.drop(columns=[self.text_column])

def pipeline():

return Pipeline([

('encode_text', TextEncoder("product_description")),

('classifier', XGBClassifier(enable_categorical=True))

])

if __name__ == "__main__":

df = pd.DataFrame({

'product_description': ['High quality wireless earbuds', 'Basic t-shirt',

'Premium smartphone with great camera'],

'average_rating': [4.5, 3.2, 4.8],

'price': [99.99, 19.99, 899.99],

'Product Category': ['Electronics', 'Clothing', 'Electronics']

})

df['Product Category'] = df['Product Category'].astype('category')

y = [1, 0, 1]

pipeline = pipeline()

pipeline.fit(df, y)

new_df = pd.DataFrame({

'product_description': ['Bluetooth headphones with noise cancellation'],

'average_rating': [4.3],

'price': [149.99],

'Product Category': ['Electronics']

})

new_df['Product Category'] = new_df['Product Category'].astype('category')

click_prob = pipeline.predict_proba(new_df)[0, 1]

print(f"Probability of click: {click_prob:.2f}")

You can run the code with the excellent uv:

uv run --script example.py

An important detail to consider is that training two models on the same data and then using the output of one model (on this same data) as input for the other can easily introduce target leakage into your pipeline. This occurs because the language model might implicitly encode the true target values, effectively revealing them to the subsequent GBDT model and leading to overfitting.

To address this issue, one solution is to split the data into two distinct parts: one for training the language model and another for the GBDT model 1. The disadvantage of this approach is that each model only utilizes a subset of the available data. A more sophisticated alternative is to employ a jackknife technique, which prevents leaking target values during the GBDT model’s training while efficiently using all available data. The downside of this approach is its computational cost, as the language model must be trained multiple times on different data batches.

It’s worth noting that this model architecture may not capture all the nuanced relationships between patterns in the text data and the structured features that are used exclusively in the GBDT model 2. Despite this limitation, I found that this approach performed remarkably well in a recent use case and was relatively straightforward to implement 3. The balance of simplicity, performance, and interpretability makes it an excellent starting point for many hybrid modeling problems.

In one of my projects, I even combined two different data sources using this approach. The first source was a very large dataset that contained only text with its ground truth (millions of data points). The second source was a much smaller dataset containing both text and additional metadata along with its ground truth. ↩︎

One might add additional features to the language model to enable feature interactions between text and structured data. ↩︎

Amazingly, this approach can be interpreted as target encoding over text instead of categorical features. ↩︎